Thinking Digitally: Chronicling the Creation of our Exhibition’s Website

As Kathleen mentioned in the last post, our exhibition will feature a digital companion meant to reflect not only the artworks installed in The Art Gallery in March, but also to make the exhibition available to people who may not have a chance to see it in person. We considered three possible platforms to host our digital site: WordPress, Omeka, and Scalar. Cecilia Wichmann and I were well placed to take the lead on this digital component, as we are both graduate assistants in the Collaboratory this fall and members of the DIG (Digital Innovation Group), in which we explore the relationship between art history and technology.

One of the central questions guiding our search for an appropriate digital companion was a simple one: How could we digitize materials in a web-friendly and accessible way, while preserving their historical integrity? We needed a platform that would allow us to accomplish three goals: the efficient organization of materials; the preservation of the exhibition’s intellectual spirit; and the creation of discursive space in which to share our curatorial point of view.

After a few weeks of research, we suggested that our class use Omeka, a free, open-source, web-publishing platform developed by the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. Omeka was created to display and store large numbers of objects and designed with libraries, archives, and museums in mind. We were particularly drawn to two of Omeka’s features: the capacity for data migration and the ability to create interactive content. To facilitate data migration, we used the CSV Import plugin[1] to quickly populate our Omeka site in a batch upload with images of the objects in our exhibition, including all appropriate Dublin Core[2] metadata.

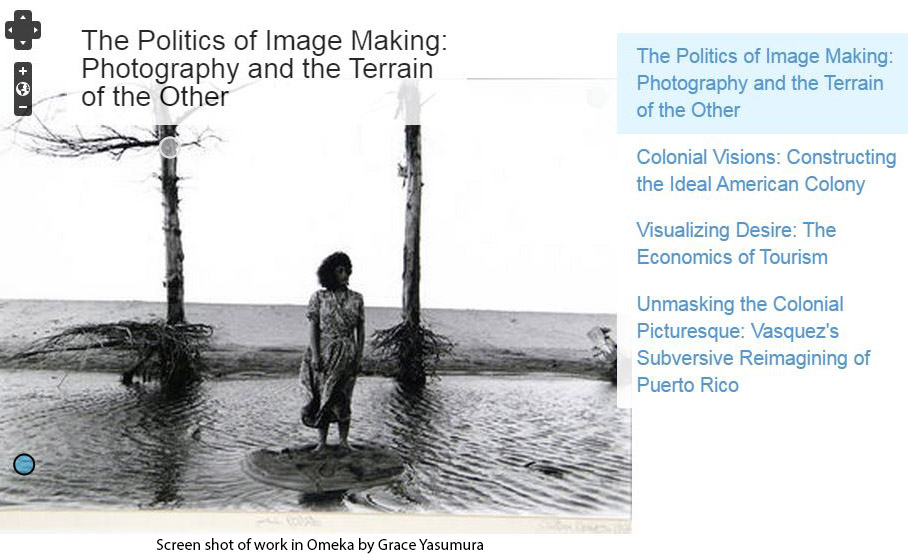

But Omeka’s most compelling features are the platform’s narrative and didactic capabilities. The Exhibit Builder plugin allows for the creation of online exhibits, or custom web pages, that attractively highlight combinations of items (including images, video, audio, PDF, and PowerPoint files) with accompanying narrative text. This exciting feature affords us the opportunity to consider alternate narratives that may be less visible in The Art Gallery due to limitations of space or to conventions of display and labeling. As we know, objects don’t just tell one story. Digital media can illuminate the complex histories and social biographies of artworks and their relationships to the spaces in which they continue to circulate. Within Omeka, the Neatline plugin facilitates the interactive and dynamic presentation of related visual materials – maps, paintings, photographs – through the artworks themselves.

I am using Neatline to create an interpretive lens through which to understand Víctor Vázquez’s Untitled. Using Neatline’s annotation tools, I have drawn translucent outlines around particularly suggestive details of Untitled (see screen shot, above). As users interact with the annotations, they will discover related image and media files that that provide supplementary details and interpretive clues. Users will also see long-format text about the specific context within which Vázquez created the work. Both the Neatline and Exhibit Builder plugins have been instrumental to our efforts to craft sophisticated and nuanced narratives about the objects in our exhibition.

As our semester comes to a rapid close, Cecilia and I are now preparing to pass our Omeka project off to Professor McEwen’s undergraduate class, who will continue to work on the exhibition in the spring semester. Our goal at the beginning of the semester was to create the framework for the exhibition’s website, including a detailed site navigation. While we have accomplished this goal, we have also been able to add other, public-facing features—a blog, interactive Neatline pages, and online gallery exhibits. Omeka has proven to be a streamlined and effective platform for our digital companion.

Credit: Grace Yasumura, Ph.D. student, University of Maryland

[2]The Dublin Core is a set of accepted terms designed to standardize the metadata ecology.