The Body in Exile

As Raino Isto and Kathleen Weigand have already discussed in their posts (accessible here and here), our seminar, led by Dr. Abigail McEwen, has focused on conversations surrounding globalization, diaspora, borderlands, and exile. The fruitful results of these conversations have underpinned our exhibition, which is broadly grouped around such themes as flows of capital, the body in exile, the agency of the object, and animals, to name but a few. In this post, I approach just one of the themes considered in the exhibition -- “the body in exile” -- and consider how two Latin American artists have entered into dialogue with it.

I begin with a disclaimer: to consider the concept of exile requires an understanding that there is not one exile but many. It is important to emphasize that exile is an individual experience and manifested in many forms. In bringing together works of art that engage with “exile,” our exhibition seeks not to homogenize such experience, but to consider together some of the commonalities of exilic experience across Latin America.

The concept of “exile” carries with it the weight of multiple associations. It can be both an internal and an external state of being, a form of punishment and of displacement. To be exiled implies a rift between the self and the home in some fundamental and irrevocable manner. It engenders dislocation, fragmentation and dispersal; affects and alters memory; and enforces separation and cultural displacement. Exile both denies an identity to a person or people and simultaneously—forcibly—forges a new kind of identity, one necessitated by geographic or psychological dislocation. For those exiled, the remembered homeland they once knew, from which they have now become alienated, is a place that no longer exists; their experiences of home are located firmly in the past and cannot be reconstructed as present-day reality.

In many of the countries of Latin America, exile has been a continuous experience since the period of colonization. Beginning in the late fifteenth century, Puerto Rico, Brazil, and the Dominican Republic, among other territories, were subjected to colonial rule by the Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch, and English; they became geographic sites over which imperial powers fought for control over three hundred years. From the subjugation endured under colonial imperialism to the mass terrorization and displacement enacted by modern dictatorial regimes (some of which remained in power until the 1990s), exile has been a corollary of continuous upheaval and instability.

The mark of exile upon Latin America’s recent history finds expression in many of the objects under consideration for our exhibition. Some works examine the multiple alienations that exile engenders and the enduring consequences of rupture and homelessness. Many of these artists turned to the body as a principal site for exploration of the social, psychological, and physical ramifications of exile; for those who have no physical location, the body has functioned as a locus of identity and stability. It is also, however, an agent that is migratory, that can transgress boundaries and borderland spaces, that is a site of power in itself. In the exhibition, one witnesses both male and female artists appropriating the body as a medium in flux, as a tool for self-representation or emphatic self-inscription capable of reclaiming an identity contrary to that of the colonized, subjugated, or subaltern.

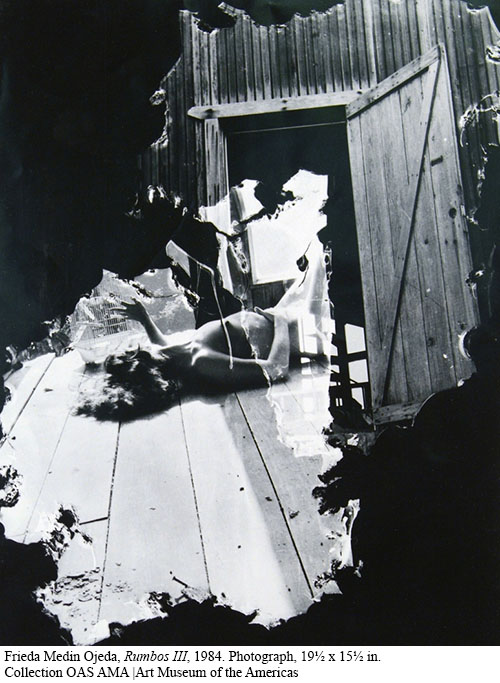

Frieda Medin Ojeda’s Rumbos III exemplifies artistic expressions of the exilic body. Born in Puerto Rico in 1949, Ojeda was educated first at the University of Puerto Rico before moving to New York to complete studies in film and video arts. Rumbos III, somewhat mysterious in its subject matter, evokes the trauma of fragmentation and exile. A woman’s body lies upon a ground line slanted at an angle, her upper torso, arms, and head visible to us but her lower body inaccessible – either fragmented or hidden, it remains unclear. The photograph itself is fragmentary, seemingly composed of a series of montaged images that simultaneously reveal and conceal the subject; she is bounded within an amorphous border that in sections seems to be a collapsed wall through which the viewer looks.

Frieda Medin Ojeda’s Rumbos III exemplifies artistic expressions of the exilic body. Born in Puerto Rico in 1949, Ojeda was educated first at the University of Puerto Rico before moving to New York to complete studies in film and video arts. Rumbos III, somewhat mysterious in its subject matter, evokes the trauma of fragmentation and exile. A woman’s body lies upon a ground line slanted at an angle, her upper torso, arms, and head visible to us but her lower body inaccessible – either fragmented or hidden, it remains unclear. The photograph itself is fragmentary, seemingly composed of a series of montaged images that simultaneously reveal and conceal the subject; she is bounded within an amorphous border that in sections seems to be a collapsed wall through which the viewer looks.

Ojeda here elicits a sense of the potential violence enacted upon the body. The woman’s position and her nakedness place her in an exposed state, a vulnerability underscored by the viewer’s privileged position of gazing at her unseen, from an unknown vantage point. The image speaks to the gendered experience of exile and to the particular dangers of violence for women dislocated from their homelands and forced into migration. The importance of differentiating between the male and female experience of exile cannot be overlooked. For many women, forced exile and migration were fraught with peril, the threats of violence and isolation heightened not only in terms of the journey “elsewhere” itself, but also in relation to societal norms in their newfound locations. Relocated to a new culture, these women found themselves as doubly “other:” living as both a woman and an immigrant in a foreign land.

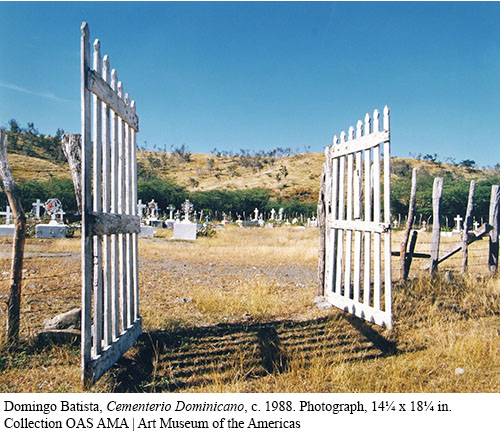

Domingo Batista’s Cementerio Dominicano also engages with the concept of exile, although here it is the total absence of the body, rather than its partiality or its embodiment, that signals fragmented experience. An open gate frames the central space of the photograph, drawing the viewer’s attention to the clusters of grave markers visible in the background. The relative emptiness of this focal point, as contrasted against the fenced space of the foreground, itself suggests a lack or an absence. The cemetery, of course, is a site of death, of the absence of the living body, and is an ultimate exilic space. Here, the body disappears, its presence in the landscape marked only by the tombstones that locate the sites of burial. The silence of this landscape marks the raw absence of the body from its space and elicits a sense of rupture, disappearance, and exile.

Domingo Batista’s Cementerio Dominicano also engages with the concept of exile, although here it is the total absence of the body, rather than its partiality or its embodiment, that signals fragmented experience. An open gate frames the central space of the photograph, drawing the viewer’s attention to the clusters of grave markers visible in the background. The relative emptiness of this focal point, as contrasted against the fenced space of the foreground, itself suggests a lack or an absence. The cemetery, of course, is a site of death, of the absence of the living body, and is an ultimate exilic space. Here, the body disappears, its presence in the landscape marked only by the tombstones that locate the sites of burial. The silence of this landscape marks the raw absence of the body from its space and elicits a sense of rupture, disappearance, and exile.

For Ojeda and Batista, amongst others in the exhibition, the theme of exile is a permeating undercurrent in their work. Many of the artworks drawn from AMA’s collection address the experiences engendered by exilic conditions, including the loss of identity, alienation, subjugation, rupture, and fragmentation. These works enter into a broader consideration of the experience of the exiled, the involuntary migrant, and the diasporic communities that result from the relocating of a people or culture.

Credit: Eleanor Stoltzfus, Ph.D. student, University of Maryland