Recovering Renart

These untitled drawings suggest . . . that life is a recalcitrant force, not to be contained or defined by attributes given it by the human mind.

Benjamin Forgey, The Sunday Star, December 5, 1965

Entering “La Casita” on November 6 for my first dive into the archive of the Art Museum of the Americas (Organization of American States), I was greeted by intrepid AMA collections curator Adriana Ospina. Adriana led me upstairs to a brightly lit landing, outfitted with a copier/scanner and desk on which she had neatly arranged what archival materials she had been able to unearth on Argentine artist Emilio Renart (1925–1991).

Entering “La Casita” on November 6 for my first dive into the archive of the Art Museum of the Americas (Organization of American States), I was greeted by intrepid AMA collections curator Adriana Ospina. Adriana led me upstairs to a brightly lit landing, outfitted with a copier/scanner and desk on which she had neatly arranged what archival materials she had been able to unearth on Argentine artist Emilio Renart (1925–1991).

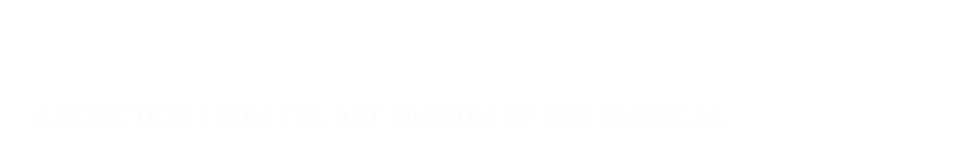

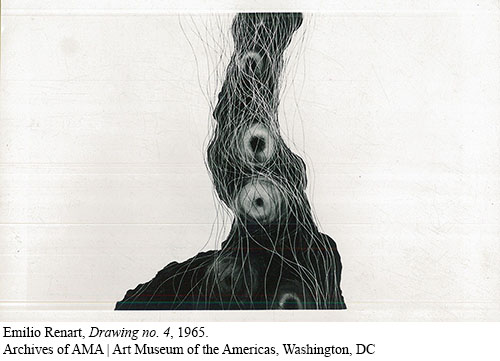

A month or so ago I had happened upon an image of Renart’s Drawing no. 13 in AMA’s onlinecollections portal and was intrigued. By the time that I encountered the work in person, a few weeks later, I had developed a minor obsession with the gossamer threads of white and ice blue inks that seem to materialize out of dark, oceanic depth and onto its raw paper surface.

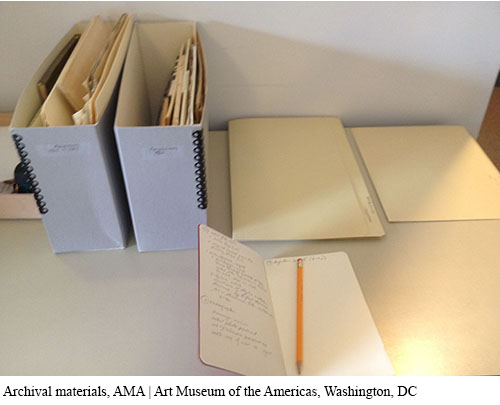

The resources now arrayed in front of us included the artist file, the exhibition file for the 1965–66 show from which Drawing no. 13 had been acquired, and country files on Argentina covering the years immediately preceding the exhibition. Adriana wasted no time in confirming what we had both suspected about records for this little-known artist and unstudied drawing: the files were slim. But Adriana said she had also found something unexpected, something tantalizing, that she knew that I would like: an envelope containing fifteen photographs associated with Renart’s exhibition.

The resources now arrayed in front of us included the artist file, the exhibition file for the 1965–66 show from which Drawing no. 13 had been acquired, and country files on Argentina covering the years immediately preceding the exhibition. Adriana wasted no time in confirming what we had both suspected about records for this little-known artist and unstudied drawing: the files were slim. But Adriana said she had also found something unexpected, something tantalizing, that she knew that I would like: an envelope containing fifteen photographs associated with Renart’s exhibition.

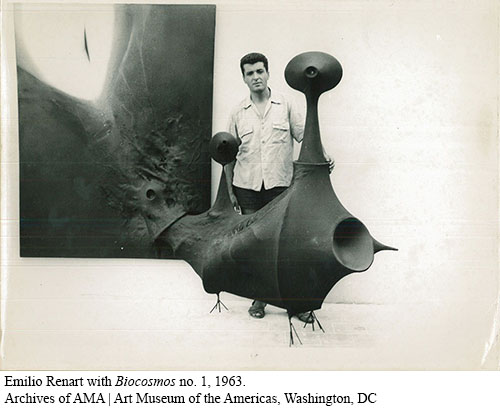

The photographs tell a curious story of absence and surrogacy. As it turns out, José Gómez-Sicre, Chief of the Pan-American Union’s Visual Arts Unit from 1948 to 1976 and organizer of Renart’s exhibition, was not primarily taken with the artist’s drawings. He settled for the exhibition of works on paper only when it proved impossible to present Renart’s series of “strange and haunting” assemblages that the artist had begun to construct in 1962. These “queer . . . objects,” which Gómez-Sicre understood as simultaneously inhabiting the worlds of painting and sculpture, could not easily be transported. They may have been impossible to reassemble without the artist present (he was apparently unable or unwilling to travel to DC), and they were too large to fit comfortably in the Pan-American Union’s exhibition hall. The photographs serve as proxies for these three-dimensional “monsters,” as Gómez-Sicre refers to them in a brochure text, or “Biocosmos,” as inscribed on the back of each black-and-white print.

The photographs tell a curious story of absence and surrogacy. As it turns out, José Gómez-Sicre, Chief of the Pan-American Union’s Visual Arts Unit from 1948 to 1976 and organizer of Renart’s exhibition, was not primarily taken with the artist’s drawings. He settled for the exhibition of works on paper only when it proved impossible to present Renart’s series of “strange and haunting” assemblages that the artist had begun to construct in 1962. These “queer . . . objects,” which Gómez-Sicre understood as simultaneously inhabiting the worlds of painting and sculpture, could not easily be transported. They may have been impossible to reassemble without the artist present (he was apparently unable or unwilling to travel to DC), and they were too large to fit comfortably in the Pan-American Union’s exhibition hall. The photographs serve as proxies for these three-dimensional “monsters,” as Gómez-Sicre refers to them in a brochure text, or “Biocosmos,” as inscribed on the back of each black-and-white print.

The photographs show three iterations within the Biocosmos series (a fourth is pictured elsewhere in the archive). In some instances, the artist is pictured, his body positioned behind or between the ridged skins and wiry cilia of these ambiguous, mammoth forms that suggest (extra-)terrestrial outcroppings, animate feelers, or perceiving machines.

The photographs show three iterations within the Biocosmos series (a fourth is pictured elsewhere in the archive). In some instances, the artist is pictured, his body positioned behind or between the ridged skins and wiry cilia of these ambiguous, mammoth forms that suggest (extra-)terrestrial outcroppings, animate feelers, or perceiving machines.

Gómez-Sicre’s desire to show Renart’s assemblages in DC by no means suggests reluctance about the drawings. Though “calmer” than the “monsters,” they are “no less intriguing” in his view and may be intimately connected, spun of the same creative DNA: “In these refined and exquisite compositions, threads interweaving like strands of silk or human hair emerge from darker zones of free forms which can be considered the nucleus of every composition. Each thread flows miraculously in a different plane. When the lines are straight and cross each other, there is the same charm and the same definition of space as in the free lines. These lines and Renart’s eye-catching concept of three-dimensional and aerial space constitute the purest elements.” The archival envelope contained three photographs of drawings likely included in the exhibition, all part of the same series as Drawing no. 13.

This cache of photographs left me with questions—what is the relation of Renart’s drawings to his assemblages? How did he achieve these fluid, interlacing lines and faulted surfaces in two and three dimensions? How might this body of work congeal an interrelation of the body, the biosphere, and the cosmos, and how do these forms signify beyond abstraction, fifty years ago and today?

This cache of photographs left me with questions—what is the relation of Renart’s drawings to his assemblages? How did he achieve these fluid, interlacing lines and faulted surfaces in two and three dimensions? How might this body of work congeal an interrelation of the body, the biosphere, and the cosmos, and how do these forms signify beyond abstraction, fifty years ago and today?

Credit: Cecilia Wichmann, Ph.D. student, University of Maryland