OBJECT ENCOUNTER: Our First Trip to the Art Museum of the Americas

This semester, the members of the graduate seminar, “Aesthetics of Exile: Borderlands, Diaspora, and Migration,” under the guidance of Dr. Abigail McEwen, have studied Latin American modernism through the lenses of various critical methodologies. We have focused on the interventions of postcolonialism; diaspora and nomadism; studies of space, displacement, and border zones; globalization; and cosmopolitanism.

This semester, the members of the graduate seminar, “Aesthetics of Exile: Borderlands, Diaspora, and Migration,” under the guidance of Dr. Abigail McEwen, have studied Latin American modernism through the lenses of various critical methodologies. We have focused on the interventions of postcolonialism; diaspora and nomadism; studies of space, displacement, and border zones; globalization; and cosmopolitanism.

In partnership with the Art Museum of the Americas (AMA) in Washington, D.C., we have a unique opportunity to apply these theories to an exhibition of our own design, to open in March 2015 at the university’s Art Gallery. We will curate this exhibition through our selection of objects from AMA’s permanent collection. The development of this show has been a main aspect of our seminar work this semester, which has included lengthy conversations on the curation of objects; the design of gallery space; the creation of a digital exhibition by Cecilia Wichmann and Grace Yasumura to accompany the university show (which Grace discusses in our next post); and the development of our exhibition proposal, the critical theory behind which Raino discusses in another post to follow.

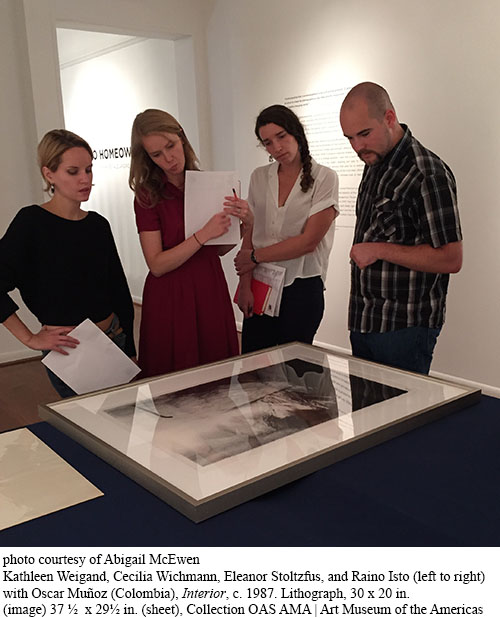

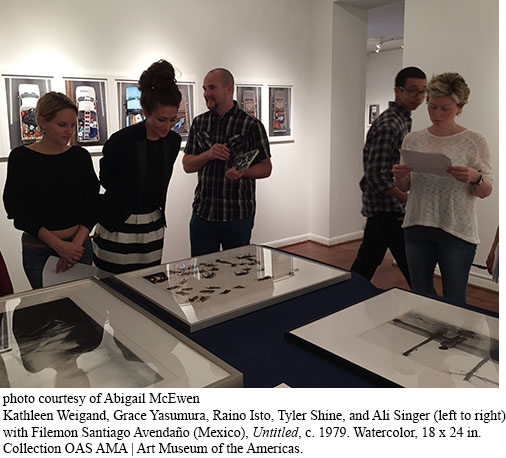

We achieved a breakthrough in our selection of objects for the exhibition during our first trip to AMA in October, when Adriana Ospina and her colleagues prepared over a dozen objects of our choosing, removing them from storage for a private viewing. Prior to our visit, we had browsed and selected a wide range of paintings, prints, and other works on paper through AMA’s collection online. It was crucial, however, that we view and discuss these selections in front of the objects themselves.

We achieved a breakthrough in our selection of objects for the exhibition during our first trip to AMA in October, when Adriana Ospina and her colleagues prepared over a dozen objects of our choosing, removing them from storage for a private viewing. Prior to our visit, we had browsed and selected a wide range of paintings, prints, and other works on paper through AMA’s collection online. It was crucial, however, that we view and discuss these selections in front of the objects themselves.

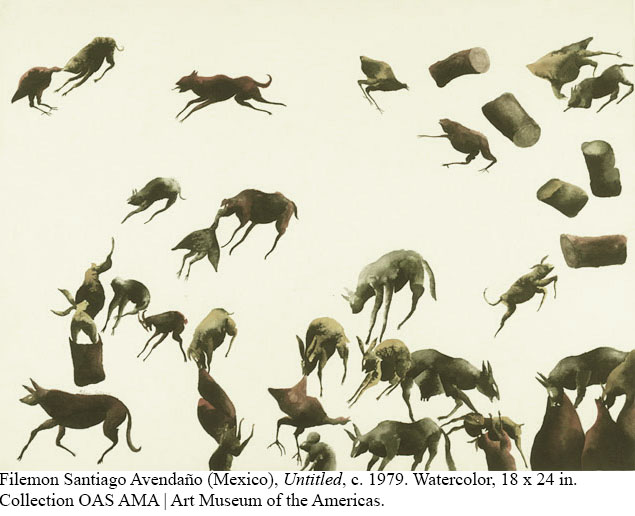

The snapshots above and below illustrate the variability of even the best digital reproductions and the importance of viewing artworks in person. Seeing their true appearance during our visit to AMA naturally led us to a more critical understanding of these objects and a revelatory reconsideration of the show. Only in person were we able to accurately apprehend the size, color, and effect of the artworks we had chosen. Our viewing of the objects also facilitated discussions of related design considerations, such as framing and matting, as well as our interest in alternative forms of display, such as the use of vitrines or monitors. Two of the group’s favorite object selections included Oscar Muñoz’s 1987 still image Interior, originally selected by Eleanor Stoltzfus, and my initial selection, Filemon Santiago Avendaño’s Untitled, a surrealistic watercolor from 1979.

Avendaño’s watercolor incorporates beautifully subtle gradations in earth tones—ochers and browns—as well as blues, greens, flashes of red, and somber greys, all of which constitute the flattened, anthropomorphic shapes of fantastic animals and surrealistic, dream-like bestial bodies. While the subtleties of color are difficult to discern in the painting’s digital reproduction, the full depth and range of color became evident upon closer inspection. Variations of recognizable forms—goats, rabbits, chickens, pigs, cats, and dogs—as well as other amalgamations of farm and domestic animals, descend together in a mass of flailing legs, ears, tongues, tails, and horns. Creatures peck, nibble, and pull at each other amidst the rush of bodies detached from space; some recede in their declination, as if tumbling from a spectral, unseen pen or precipice. In the upper right-hand corner, bizarre, block-like forms and incomplete animal bodies evoke a sense of amputation and slaughter, while the frenetic mass of seemingly carnivorous creatures, and their carnal contact with one another, elicit a sense of the “uncanny strangeness” discussed by Julia Kristeva in her discourse on cosmopolitanism.[1]

Avendaño’s watercolor incorporates beautifully subtle gradations in earth tones—ochers and browns—as well as blues, greens, flashes of red, and somber greys, all of which constitute the flattened, anthropomorphic shapes of fantastic animals and surrealistic, dream-like bestial bodies. While the subtleties of color are difficult to discern in the painting’s digital reproduction, the full depth and range of color became evident upon closer inspection. Variations of recognizable forms—goats, rabbits, chickens, pigs, cats, and dogs—as well as other amalgamations of farm and domestic animals, descend together in a mass of flailing legs, ears, tongues, tails, and horns. Creatures peck, nibble, and pull at each other amidst the rush of bodies detached from space; some recede in their declination, as if tumbling from a spectral, unseen pen or precipice. In the upper right-hand corner, bizarre, block-like forms and incomplete animal bodies evoke a sense of amputation and slaughter, while the frenetic mass of seemingly carnivorous creatures, and their carnal contact with one another, elicit a sense of the “uncanny strangeness” discussed by Julia Kristeva in her discourse on cosmopolitanism.[1]

This “uncanny strangeness” of the nomadic artist’s encounter with other cultures is readily identifiable in his biography. A Mexican-born resident of Oaxaca, Avendaño spent much of his early artistic training and career in Chicago. In 1995, Avendaño’s “cosmopolitan” career took him to the Netherlands as a professor. He has since reclaimed Oaxaca as his permanent residence and workplace. The Art Institute of Chicago is one of several American institutions to collect his work.

Through our exhibition, we hope to bring rarely exhibited objects such as Avendaño’s watercolor to the university and the greater public. In foregrounding contemporary Latin American artists, often little known in the United States, and the critical discourse around them, we also hope to draw new connections within and between the university and its neighboring communities.

Credit: Kathleen Weigand, Ph.D. student, University of Maryland