Hybridity and Exile in María Martínez-Cañas' Photomontage

Last fall, I had the opportunity to visit the archives at AMA to research a handful of artists for Streams of Being. Each time the archivists brought out a new folder, they reminded me to be attentive to the order of its contents, prompting me to visualize the ways in which we might think of each folder as a fluid text in and of itself. The loose documents read like the pages of an artist’s book, with pieces added as AMA acquired them. Yet the narratives nonetheless remain fragmentary, almost like a photomontage. What I became more interested in as I read and studied each new document, each new trace of some history, were the spaces in-between this narrative. Michel Foucault, in his text The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969), envisions the archive as a way of studying, or constructing the past to shape meaning. Foucault’s definition allows us to further think about the archive as a space of making. One of the artists in our exhibition, María Martínez-Cañas, has helped to shape my own ideas about this exhibition through her own work, which acts as just such a constructed archive. In particular, her photomontage Fragment Pieces #4 fits into a larger artistic narrative in which the medium of photography, and any singular image, is pointedly relegated.[1] In its place, she often draws on her own histories, both personal and collective, tapping into many of the themes we studied throughout our seminar: exile and diaspora, global and local histories. Her work strikes a balance between her own biography and the ways in which the objects themselves have meaning and agency, a theme that Raino Isto has explained here.

Last fall, I had the opportunity to visit the archives at AMA to research a handful of artists for Streams of Being. Each time the archivists brought out a new folder, they reminded me to be attentive to the order of its contents, prompting me to visualize the ways in which we might think of each folder as a fluid text in and of itself. The loose documents read like the pages of an artist’s book, with pieces added as AMA acquired them. Yet the narratives nonetheless remain fragmentary, almost like a photomontage. What I became more interested in as I read and studied each new document, each new trace of some history, were the spaces in-between this narrative. Michel Foucault, in his text The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969), envisions the archive as a way of studying, or constructing the past to shape meaning. Foucault’s definition allows us to further think about the archive as a space of making. One of the artists in our exhibition, María Martínez-Cañas, has helped to shape my own ideas about this exhibition through her own work, which acts as just such a constructed archive. In particular, her photomontage Fragment Pieces #4 fits into a larger artistic narrative in which the medium of photography, and any singular image, is pointedly relegated.[1] In its place, she often draws on her own histories, both personal and collective, tapping into many of the themes we studied throughout our seminar: exile and diaspora, global and local histories. Her work strikes a balance between her own biography and the ways in which the objects themselves have meaning and agency, a theme that Raino Isto has explained here.

A topic that we explored in theoretical depth last semester, the theme of exile runs throughout our exhibition. In this regard, the medium of photomontage has been particularly important to Martínez-Cañas because, as she says, it helps her “to create new memories that have to do with who I am.” Artists have often used the medium as a form of political protest, and Andy Grundberg suggests that perhaps the majority of these artists were also in exile or refugees.[3] From this perspective, Martínez-Cañas engages her historical ties to a larger network of artists in exile at the level of medium. We can see the fragmentary nature of her photomontage technique as operating at this initial level: the work exists as a single fragment of a larger narrative of artists in exile linked through this condition of medium specificity.

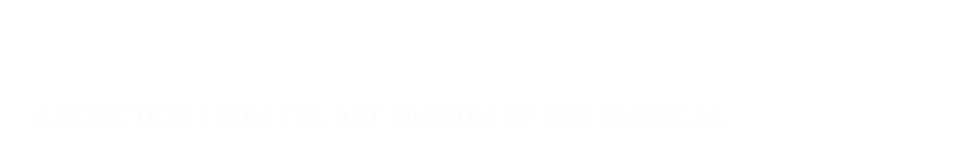

The images within the piece itself are also significant in their representation of the intellectual trajectory of our class as we shaped this exhibition. The photographs depict pre-Columbian objects, suggesting a historical and hemispheric link for Martínez-Cañas as a Latin American artist. The written text above and below the object on the left reads, “That which narrates can make us understand. The primitive begins alone; he inherits no practice.” The notion of inheriting practice subtly implies cultural hybridity, whereas “beginning” and “alone” taken together describe points of origin unfettered by outside input. Cultural hybridity as well as the complex relationship between the local and the metropolitan, as we explored through the work of writers such as Fredric Jameson and Arjun Appadurai, resonated at the fore of our thinking around this exhibition. Martínez-Cañas’ piece speaks well to these larger themes as the text, visually paired with pre-Columbian objects, engages to one half of the equation: the indigenous. Yet the text also foreshadows later European conquest, particularly in the use of the word “primitive,” a European notion that relegated indigenous populations to a presumptively less civilized, and thus lower, social standing.

Many of the artists in this exhibition deal with notions of cultural hybridity. Hybridity implies an initial flow and movement, perhaps due to exile or immigration, or even the liminal condition of the refugee. Martínez-Cañas was born in Cuba, but she and her family fled to Puerto Rico as exiles shortly thereafter. Thus, she has lived not only a life in exile but also one defined by cultural hybridity. She moved to the United States only a few years before she produced Fragmented Pieces #4, a work that frames and augments the feeling of displacement. The photomontage medium, as adapted in this piece, allows us to imagine the work itself as expressing a kind of hybridity.[4] The image of the book onto which Martínez-Cañas has placed the pre-Columbian images returns me again to the notion of the archive and the experience of flipping through the various fragments contained within each folder, a metaphorical “artist’s book.” Fragmented Pieces #4 is emblematic of the themes and ideas we explored together as a class and, at a personal level, it registers the ways in which my thinking has been further shaped through the use of AMA’s archives. My visit to AMA was crucial to my understanding of individual artists work. Tellingly, it also inspired new creative conjunctions between an artist, as pieced together by the archive, and the fragmented narratives and cultural fragmentation as experienced by an artist (herself) in exile.

Credit: Alison Singer, Ph.D. student, University of Maryland

[1] Although this specific piece is not included in our exhibition, this work by Martínez-Cañas expresses many of the themes central to our exhibition and guided my thinking during the course of my research in the archives at AMA.

[2] Andy Grundberg, “A Storm of Images: the Photographs of María Martínez-Cañas,” in María Martínez-Cañas: A Retrospective, April 30 – July 28, 2002 (Fort Lauderdale: Museum of Art, 2002).

[3] Andy Grundberg, “A Storm of Images: the Photographs of María Martínez-Cañas.”

[4] Olga M. Viso, “With Feet Firmly Planted,” in María Martínez-Cañas: A Retrospective, April 30 – July 28, 2002 (Fort Lauderdale: Museum of Art, 2002).